Lightning is one of those things that still feels like magic, even when we know the science behind it. A sudden bolt splits the sky, a rumble shakes the windows, and it’s over before your brain can fully process it. But inside that fleeting second, there’s a whole sequence of microscopic and incredibly fast steps going on. Each flash of lightning is like a well-rehearsed dance between the clouds and the ground, only it’s happening at speeds of thousands of kilometres per second and in bursts that last millionths of a second.

Let’s break it down and zoom right in, right into the guts of a lightning strike.

It all starts in the clouds

The storm clouds, or cumulonimbus clouds if you’re feeling fancy, are a hive of chaos. Updrafts and downdrafts inside the cloud slam ice particles into each other, causing electrons to be knocked loose. These electrons collect at the base of the cloud, making it negatively charged. Meanwhile, the top of the cloud becomes positively charged, and so does the ground directly below the cloud, because the negative charge in the cloud repels electrons in the Earth’s surface, leaving it positive.

So now you’ve got a battery of sorts. A massive, unstable, natural battery that’s itching to spark.

But the air between the cloud and the ground? That’s an insulator. Normally, it stops electricity from flowing. However, when the electric field gets strong enough – about 3 million volts per metre, it breaks down the resistance of the air. And then the show begins.

Enter the stepped leader

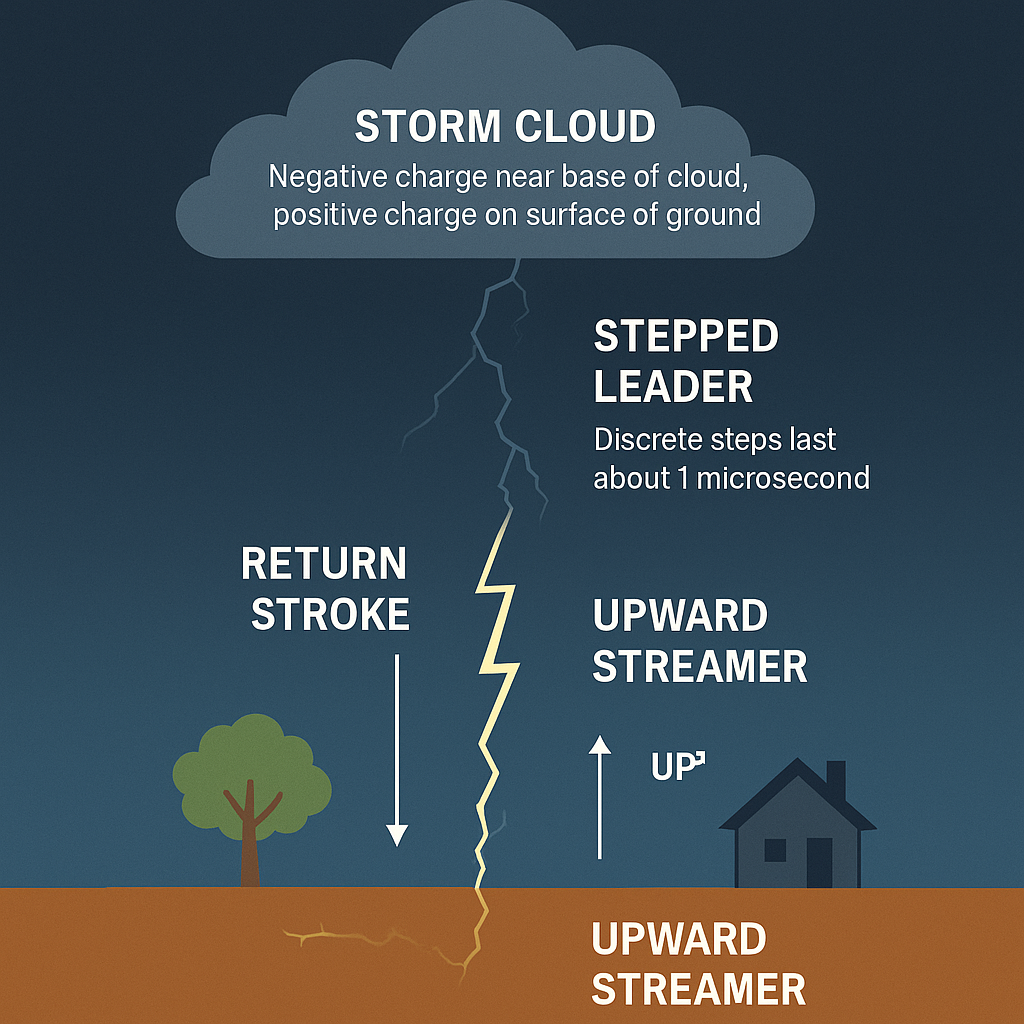

The very first visible sign of a lightning strike isn’t actually visible to the naked eye, because it’s so faint and quick. It’s called the stepped leader. This is a channel of ionised air that snakes its way down from the cloud toward the ground in a jagged, forking path. Each step is about 50 to 100 metres long and takes around 1 microsecond to form. There’s a short pause between each step, another 50 microseconds or so before the next segment shoots forward.

This continues for several milliseconds, and by the time the leader is near the ground. Maybe within 100 metres or so, something strange happens. The electric field at the surface of the Earth becomes so intense that positive streamers (think of them like tiny arms of charge) leap upward from tall objects, trees, rooftops, even the ground itself.

The connection and the return stroke

Eventually, one of these upward streamers meets the downward-stepping leader. When that connection is made, somewhere up in the air, maybe 30-100 metres above the ground, the path is complete. The channel is now open from the cloud to the ground.

This is when the big flash happens. The return stroke. Electricity from the ground races upward toward the cloud through that ionised path at speeds of about 100,000 km per second. It’s that upward surge that you actually see as the blinding flash. It travels back up the path the leader created, lighting it up like a string of firecrackers going off in reverse.

This return stroke lasts for about 30 to 100 microseconds. It’s bright, hot – about 30,000°C, and it’s why trees explode, sand fuses into glass, and electrical systems go haywire.

Multiple strokes: lightning’s encore

But it often doesn’t end there. The initial channel can remain open for a bit, milliseconds again. If the energy imbalance in the cloud hasn’t been fully equalised, more leaders can follow that same path, and more return strokes can occur. That’s why lightning often looks like it flickers. It’s not one flash, it might be three, four, or even a dozen strokes following the same channel in quick succession.

Each of those strokes takes about the same time; tens of microseconds, but they come one after the other every 30 to 50 milliseconds. That strobing effect is part of what makes lightning so mesmerising.

After the bang

Once the charge has neutralised enough, the whole system settles down. The channel collapses. The thunder you hear is the sound of the superheated air expanding faster than the speed of sound; basically a shockwave.

The whole thing, from leader formation to the final stroke, might last half a second. Maybe a bit longer. But inside that half-second are dozens of microsecond events, each critical to the spectacle we see from miles away.

So the next time you see a flash of lightning, remember this: by the time you blink, that stepped leader’s already made its way down, the ground has responded, and an explosion of energy has raced back up at near light-speed. It’s a whole storm of tiny events packed into one brilliant moment.

Now here’s something to chew on: if the return stroke goes up from the ground to the cloud, why do we see the lightning bolt going down? Could our eyes and brain be playing catch-up with nature’s sleight of hand?