Join the Weather Lovers Community at Skool

Professor Gordon Manley (1902 – 1980)

Gordon was born on 3 January 1902 in Douglas on the Isle of Man but grew up just across on the mainland in Blackburn, Lancashire. He attended Queen Elizabeth’s Grammar School before heading off to Manchester University to study engineering—he graduated in 1921. Then he switched fields, going on to Cambridge and earning a double-first in geography by 1923. He briefly joined the Met Office in 1925 (stationed at Kew Observatory), but he handed in his notice the following year, having caught the academic spark.

It was in 1926 that he joined the Cambridge expedition to East Greenland, where on Sabine Island he cut his teeth in some serious weather research. That same year, he took up an academic post at Birmingham.

A couple of years later he landed at Durham University (in 1928), where he set up the Geography Department and became the curator of the Durham University Observatory. That’s where he began to turn long-held temperature records into proper, comparable climate series—keen attention to detail, note by note.

He didn’t just rely on dusty archives—he was often out in the wilds, too. In the early 1930s he gathered data at Moor House in the North Pennines, and later at Great Dun Fell, where he ran hourly observations from 1938 to 1940. He even studied the Helm Wind—that fierce north-easterly gust over Cross Fell—and captured it in terms of fluid dynamics as a standing wave and rotor. All of this showed him as a scientist who walked alongside the elements, not just studied them from afar.

By 1939, he’d moved to Cambridge University. During the Second World War he became a lieutenant in the University Air Squadron while still teaching and continuing his research. After the war, he served as President of the Royal Meteorological Society and helped launch the Society’s magazine Weather in 1946.

In 1948 he became Professor of Geography at Bedford College, University of London—a post he held until 1964. It wasn’t until then that he took on the challenge of founding a new Department of Environmental Studies at the fledgling University of Lancaster. He retired in 1967, returning to Cambridge, but stayed on as a research associate.

His most enduring legacy? The Central England Temperature (CET) series, stretching all the way back to 1659—a record that spanned centuries and continues to be used today as a yardstick for evaluating both past and future climate change. He assembled it over three decades, and it remains the oldest long-term, standardized instrument-based climate record in the world.

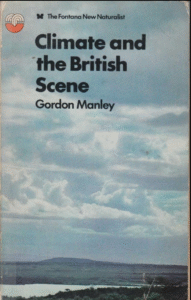

There was also Climate and the British Scene, published in 1952 as part of Collins’s New Naturalist series. It shares the gentle rhythm of British seasons with curious elegance—sunshine and mist, rain and hail—and does it in a way that speaks to both the knowledgeable and the curious reader. He also wrote a string of thoughtful pieces for the Manchester Guardian from the early 1950s onwards—weather as narrative, not just a forecast.

There was also Climate and the British Scene, published in 1952 as part of Collins’s New Naturalist series. It shares the gentle rhythm of British seasons with curious elegance—sunshine and mist, rain and hail—and does it in a way that speaks to both the knowledgeable and the curious reader. He also wrote a string of thoughtful pieces for the Manchester Guardian from the early 1950s onwards—weather as narrative, not just a forecast.

Even after retirement, Manley stayed restless—in the best of ways. He carried on publishing into the late 1960s and beyond. He served as a visiting professor in meteorology in Texas around 1969–70. He wrote over 180 articles from the late 1920s right up until his final days.

Then on 29 January 1980, he passed away in Cambridge—closing a chapter on one of Britain’s most faithful archivists of its weather.

There’s something in his story that warms my weather geek heart. Here’s a man who saw the climate as both story and data, who measured snow and wind, who even felt the rhythms of snowfall through history.

Join the Weather Lovers Community at Skool