Join the Weather Lovers Community at Skool

On most winter mornings you can stroll down from Durham city centre, past the Botanic Garden, through the woods, and by the time you reach the meadows at Houghall your breath hangs heavier and your toes feel that extra bite. It’s not your imagination. Houghall is a frost hollow – and one of the most efficient in the North East.

The Met Office even have it on their books. Back on 5 January 1941, Houghall recorded an incredible –21.1°C, a North East record that still stands today. That’s the kind of number that makes you wonder how anyone got out of bed. The set-up is simple on paper, but powerful when it plays out.

When the sun drops, the ground begins to lose heat to the clear night sky. The thin layer of air in contact with the grass cools first. As it cools, it gets heavier and starts to slide downhill like treacle poured from a spoon. In meteorology we call that katabatic drainage. At Houghall, that cold air drains off the higher ground around Mountjoy, the Botanic Garden, and Low Burnhall, then gathers in the meadows by the River Wear.

The loop of the river and the gentle bowl of the land act like the sides of a bath. Trees and banks keep the wind down, so the cold air isn’t stirred up and mixed away. Over the hours, the pool of cold deepens. An inversion forms – cold air below, milder air above. If a mist forms in the hollow, it works like a lid on a saucepan, slowing any warming and helping the frost thicken.

On a still, clear winter’s night, it’s common for Houghall to be several degrees colder than the city centre. Throw in a thin layer of snow and the numbers really drop, because snow loses heat even faster and reflects sunlight in the day, stopping any quick thaw.

Houghall isn’t alone.

The UK has several other famous frost hollows:

* Benson, Oxfordshire – Low in the Thames Valley, it’s known for sharp frosts and often records the coldest readings in the south on calm, clear nights.

* Rickmansworth, Hertfordshire – Once had a railway embankment acting like a dam, trapping cold air in the valley bottom and making for big temperature drops.

* Shap, Cumbria – Higher up, but surrounded by gentle slopes that feed cold into shallow basins. Not as extreme as Houghall’s 1941 reading, but a consistent freezer.

* Braemar, Aberdeenshire – The UK cold champion, sitting in a high glen that can hold cold for days. Different scale, same physics.

What makes Houghall special is how close it is to the heart of Durham. In ten minutes you can walk from the bustling market square to a spot that on the right night feels like a different climate altogether.

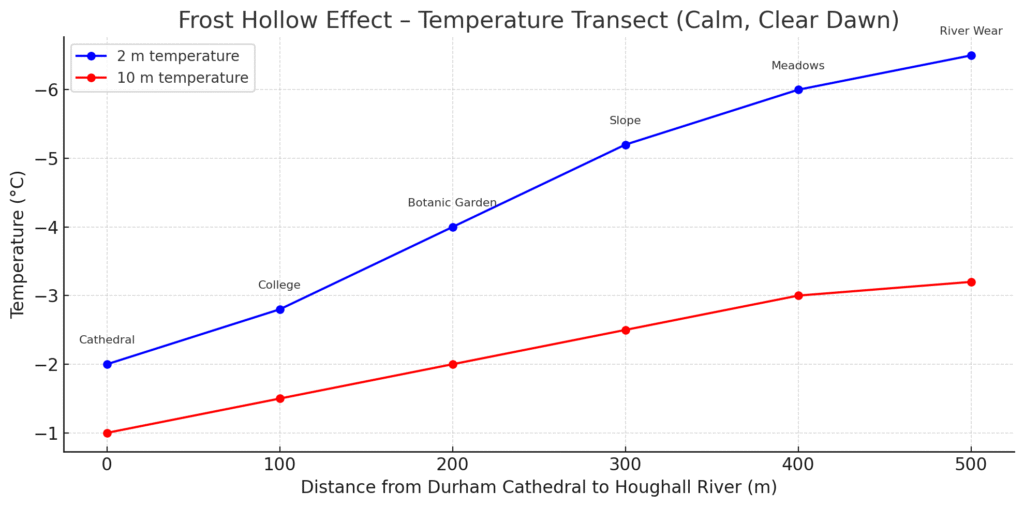

If you want to see the effect for yourself, try a little experiment this winter. Take a cheap thermometer and note the temperature outside Durham Cathedral just after dawn on a calm, clear morning. Then head down to the Houghall meadows and check again. If the weather’s playing ball, you’ll see a gap of three or four degrees – sometimes more.

I’d love to set up a line of sensors from the Botanic Garden entrance down to the river path one frosty night, to capture the build-up of that cold pool hour by hour. I reckon it would be one of the most revealing microclimate profiles in the county.

It’s easy to miss microclimates like Houghall unless you know where to look, but once you’ve felt one, you never forget it. Makes you wonder – how many other little cold traps are lurking in the folds of County Durham?

Here’s the temperature transect, showing how much colder it gets as you drop from the Cathedral down to the Houghall meadows, and how the inversion keeps the air aloft several degrees milder.

MORE READING : THE HISTORY OF EAST DURHAM COLLEGE’S HOUGHALL CAMPUS

Join the Weather Lovers Community at Skool